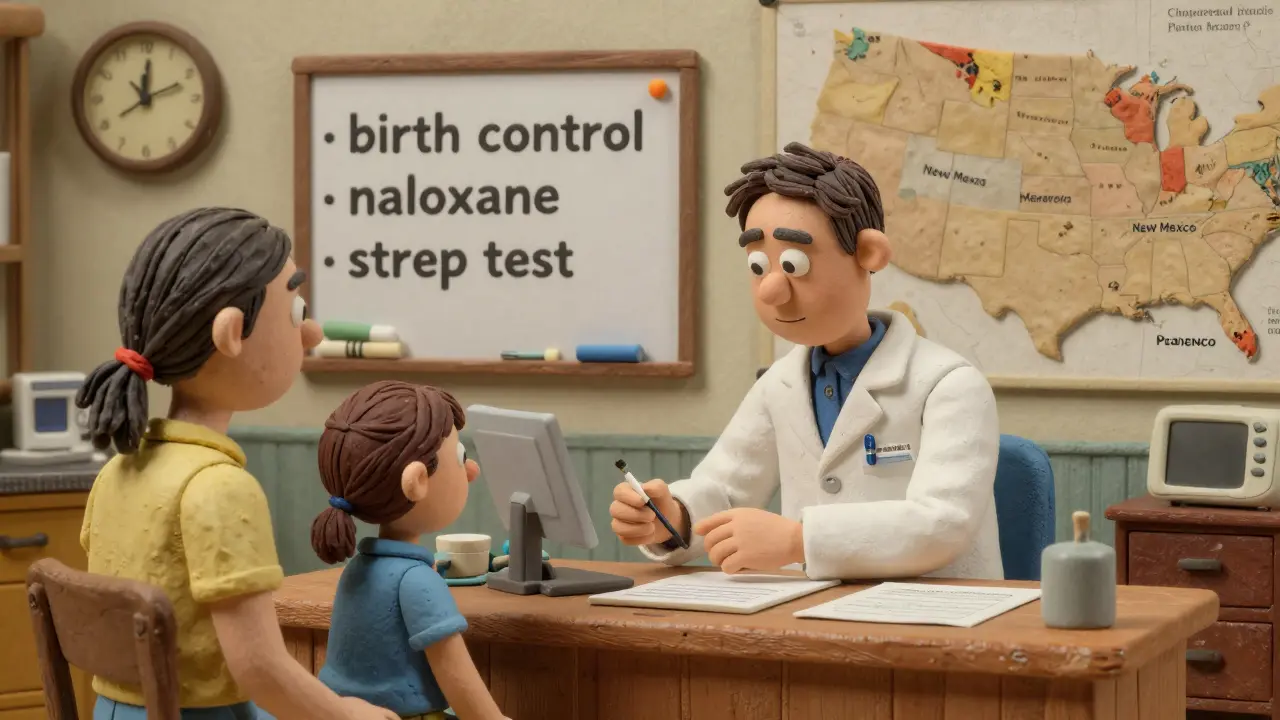

For decades, pharmacists were seen as the people who counted pills and handed out prescriptions. But today, in many parts of the U.S., they’re doing far more - adjusting medications, prescribing birth control, dispensing naloxone without a doctor’s note, and even running basic health screenings. This shift isn’t random. It’s the result of deliberate legal changes that expand what pharmacists are allowed to do under their scope of practice. Understanding these changes matters - whether you’re a patient, a healthcare worker, or just someone trying to get care faster.

What Exactly Is Pharmacist Substitution Authority?

Pharmacist substitution authority means the legal right for pharmacists to change or swap a prescribed medication under specific rules. It’s not about making random choices. Every swap has to follow state laws, clinical guidelines, and often, written agreements with doctors. The most basic form is generic substitution. If your doctor prescribes Lipitor, and there’s a generic version of atorvastatin available, the pharmacist can give you that instead - unless the doctor wrote "dispense as written" on the prescription. This is allowed in every state. But it goes further. Some states let pharmacists do therapeutic interchange. That means swapping one drug for another in the same class, even if they’re not chemically identical. For example, switching from one blood pressure medication to another because the first one caused side effects or is too expensive. Only three states - Arkansas, Idaho, and Kentucky - have full therapeutic interchange laws as of 2025. In Kentucky, the doctor must write "formulary compliance approval" on the script. In Idaho and Arkansas, they must say "therapeutic substitution allowed." And in all three, the pharmacist has to tell the prescribing doctor and get the patient’s consent before making the switch.How States Are Expanding What Pharmacists Can Do

States aren’t waiting for Congress to act. They’re passing laws on their own. In Maryland, pharmacists can prescribe birth control to adults without a doctor’s involvement. In Maine, they can hand out nicotine patches for quitting smoking. California lets pharmacists "furnish" certain drugs - a legal term that avoids calling it "prescribing" but means the same thing in practice. New Mexico and Colorado take a different route. Instead of passing new laws for every new service, their boards of pharmacy create statewide protocols. If a pharmacist completes the training, they can provide things like flu shots, emergency contraception, or even treat strep throat - all under the same set of rules that can be updated without going back to the legislature. The most advanced model is independent prescribing. All 50 states and D.C. now allow pharmacists to prescribe or dispense medications under some kind of protocol. These aren’t just for vaccines anymore. In many states, pharmacists can start, stop, or change medications for conditions like diabetes, high cholesterol, or hypertension - if they’ve been trained and have a written agreement with a doctor or a statewide standing order.Collaborative Practice Agreements: The Hidden Engine Behind the Change

You won’t hear much about Collaborative Practice Agreements (CPAs), but they’re the backbone of expanded pharmacy practice. A CPA is a written contract between a pharmacist and one or more doctors that outlines exactly what the pharmacist can do. It includes things like which drugs they can prescribe, what lab tests they can order, when they must refer a patient to a doctor, and how they document everything. These agreements aren’t the same everywhere. In some states, the doctor has to sign off on every decision. In others, the pharmacist runs the show - as long as they follow the protocol. Recent trends show a clear shift: pharmacists are getting more autonomy within CPAs. Less oversight. More responsibility. That’s because studies show that when pharmacists manage chronic conditions like asthma or diabetes, patients have better control of their numbers and fewer hospital visits.

Why This Matters: Access, Equity, and Shortages

There’s a reason all this is happening. The U.S. is facing a massive shortage of primary care doctors. By 2034, the Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a shortfall of 124,000 physicians. Rural areas are hit hardest - 60 million Americans live in places where there aren’t enough doctors. In these communities, the nearest pharmacy might be the only place you can get care. Pharmacists are already there. They’re open longer hours. They don’t need appointments. They’re trained to spot drug interactions, side effects, and adherence problems. When a pharmacist can adjust a dose, refill a prescription, or start a treatment for strep throat or a yeast infection, patients don’t have to wait weeks for a doctor’s slot or drive an hour to a clinic. This isn’t just convenient - it’s life-saving. In states where pharmacists can dispense naloxone without a prescription, overdose deaths have dropped. Where they can prescribe birth control, unintended pregnancies have decreased. In places with high rates of diabetes, pharmacist-led management has improved HbA1c levels as much as doctor-led care.The Pushback: Who Opposes This and Why?

Not everyone is on board. The American Medical Association still has a policy to study pharmacists who refuse to fill prescriptions - a move many see as targeting pharmacists who decline to dispense emergency contraception or abortion-related drugs on moral grounds. But beyond that, there’s a deeper concern: Are pharmacists qualified to make clinical decisions? Some doctors argue that pharmacists don’t have the same training as physicians. That’s true - but it’s also misleading. Pharmacists don’t need to diagnose a broken bone. They need to know how drugs interact, how kidneys process medications, how age and weight affect dosing. That’s their specialty. Their education includes four years of pharmacy school plus clinical rotations. Many now have postgraduate training in areas like cardiology or infectious disease. The real issue isn’t training - it’s turf. Some physicians worry that pharmacists stepping into prescribing roles will erode their income or authority. Corporate pharmacy chains, on the other hand, have been strong supporters. They see expanded roles as a way to keep patients in their stores, increase foot traffic, and justify higher reimbursement rates.

Biggest Hurdle: Getting Paid for What They Do

Here’s the catch: just because a pharmacist can prescribe a drug doesn’t mean insurance will pay for it. Most private insurers and Medicare still don’t recognize pharmacists as providers. They’ll pay for the pill - but not for the time, counseling, or monitoring that comes with it. That’s where the federal Ensuring Community Access to Pharmacist Services Act (ECAPS) comes in. If passed, it would require Medicare Part B to reimburse pharmacists for services like testing, vaccinations, and chronic disease management. That’s a game-changer. If Medicare pays, private insurers will follow. States like Maryland and Maine already require Medicaid to cover pharmacist services - but without federal backing, it’s patchwork.What You Need to Know as a Patient

If you’re on a long-term medication and your pharmacist suggests a switch - whether it’s a generic version or a different drug in the same class - ask why. They’re required to explain the change, tell you about potential side effects, and confirm you’re okay with it. You have the right to say no. If you live in a rural area or have trouble getting to a doctor, ask your pharmacist if they can help with refills, dose changes, or even basic health checks. In many places, they can. And if you’re prescribed something like birth control or naloxone and the pharmacist says they can’t provide it - that’s not legal in states that allow it. Know your rights.What’s Next?

The trend is clear: pharmacists are becoming frontline providers. The next five years will see more states adopt therapeutic interchange, independent prescribing, and statewide protocols. Reimbursement will slowly catch up - especially if ECAPS passes. But success won’t come from laws alone. It’ll come from better communication between pharmacists and doctors, clearer documentation, and patients who understand what pharmacists can now do. This isn’t about replacing doctors. It’s about using every trained professional to their full potential. When pharmacists can act within their expertise, everyone wins - patients get faster care, doctors get fewer routine tasks, and the system becomes less broken.Can a pharmacist change my prescription without telling my doctor?

No. Even in states with broad substitution authority, pharmacists must notify the prescribing provider when they make any therapeutic change - whether it’s a generic swap or switching to a different drug in the same class. In most cases, they’re also required to document the change in the patient’s record and, in some states, get the patient’s consent before proceeding.

Which states allow pharmacists to prescribe birth control?

As of 2025, at least 24 states and the District of Columbia allow pharmacists to prescribe hormonal birth control without a doctor’s prescription. Maryland was the first to pass such a law, explicitly labeling pharmacists as "providers" under Medicaid. Other states include California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, and New Mexico. Rules vary - some require a brief health screening, others require a completed questionnaire. Always check your state’s current laws.

Do pharmacists need special training to prescribe medications?

Yes. In states that allow independent prescribing or therapeutic interchange, pharmacists must complete additional training - often 15 to 40 hours of continuing education focused on diagnosis, treatment protocols, and clinical decision-making. Some states require certification in areas like diabetes management or cardiovascular care. Many pharmacists now hold postgraduate certificates or even doctorates in clinical pharmacy.

Can a pharmacist refill my prescription without a doctor’s approval?

In limited cases, yes. Many states allow pharmacists to extend refills for chronic medications like blood pressure or thyroid drugs if the patient is out of refills and unable to reach their doctor. This is called "prescription adaptation." But it only applies to specific conditions, and the pharmacist must document the change and notify the prescriber within a set timeframe - usually 24 to 72 hours.

Why don’t insurance companies pay pharmacists for their services?

Most insurance systems still classify pharmacists as dispensers, not providers. They pay for the drug, but not for the time spent counseling, adjusting doses, or managing chronic conditions. Medicare doesn’t reimburse for pharmacist services under Part B - yet. That’s changing slowly, with Medicaid leading the way in some states. The federal ECAPS bill, if passed, would force Medicare to pay for pharmacist services, which would likely push private insurers to follow.