Opioid Dose Adjustment Calculator

Dose Calculator

When someone has liver disease, taking opioids isn’t just riskier-it can be dangerous in ways most people don’t expect. The liver doesn’t just filter toxins; it’s the main factory that breaks down opioids. When it’s damaged, those drugs don’t clear the way they should. Instead, they build up. And that buildup can lead to overdose, confusion, breathing problems, or even death-even at doses that are perfectly safe for someone with healthy liver function.

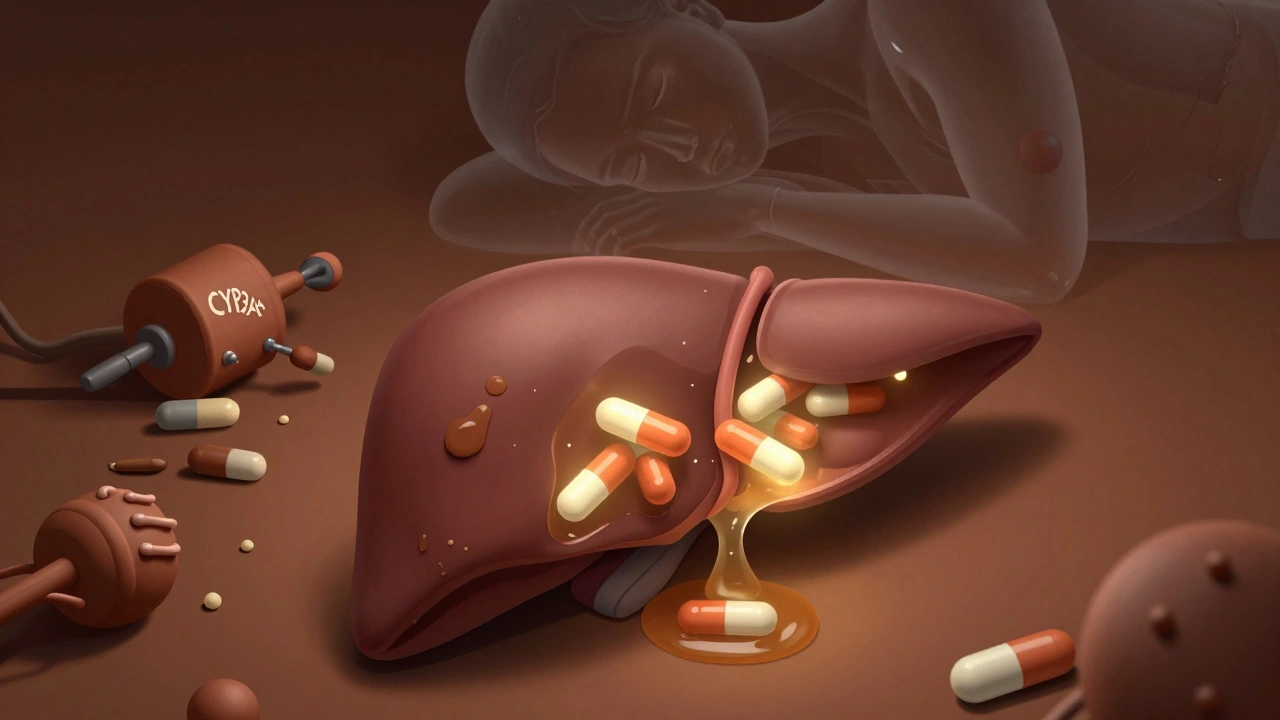

How the Liver Normally Processes Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to break down opioids: cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are like specialized machines that chop up drug molecules so they can leave the body through urine or bile. Morphine, oxycodone, and methadone all rely on these systems-but they use different ones. Morphine gets turned into morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which is even stronger than morphine itself, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which can cause seizures and nerve damage. Oxycodone is mainly broken down by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Methadone uses several enzymes at once, which makes its behavior harder to predict.

When the liver works well, these processes happen quickly. But in liver disease, the machines slow down-or stop. That means the drugs stay in the bloodstream longer. For example, in someone with normal liver function, oxycodone lasts about 3.5 hours. In severe liver disease, that time jumps to 14 hours on average, and can stretch as long as 24.4 hours. That’s more than six times longer.

What Happens When the Liver Can’t Keep Up

As liver damage gets worse, opioid clearance drops. Studies show that in advanced cirrhosis, morphine’s half-life can double or triple. The same thing happens with oxycodone: peak levels in the blood rise by up to 40%. This isn’t just a minor delay. It means the drug keeps acting on the brain and lungs far longer than intended. The result? Sedation, low breathing rates, and loss of consciousness become much more likely-even with small doses.

Some opioids create toxic byproducts. Morphine’s M3G metabolite doesn’t help with pain-it just harms nerves. In healthy people, the body clears M3G fast. In liver disease, it piles up. That’s why some patients on long-term morphine develop unexplained muscle twitching, seizures, or extreme sensitivity to pain. These aren’t side effects of the pain itself-they’re signs the liver can’t handle the drug.

Different Liver Diseases, Different Risks

Not all liver damage is the same. The type of disease changes how opioids are processed. In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is linked to obesity and diabetes, CYP3A4 activity drops by up to 50%. That means drugs like oxycodone and fentanyl stick around longer. In alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), the opposite happens: CYP2E1 becomes overactive. This enzyme can turn some opioids into more toxic forms and also increases oxidative stress, which worsens liver damage.

Chronic opioid use itself may make liver disease worse. Studies now show opioids change the gut microbiome-the trillions of bacteria living in the intestines. When those bacteria get out of balance, they leak harmful substances into the portal vein, which leads straight to the liver. This triggers inflammation, speeds up scarring, and makes fatty liver turn into cirrhosis faster. It’s a vicious cycle: liver disease makes opioids more dangerous, and opioids make liver disease worse.

Which Opioids Are Safest-And Which to Avoid

Not all opioids are created equal when the liver is failing. Morphine is one of the riskiest because of its reliance on glucuronidation, which shuts down early in liver disease. Even small doses can lead to dangerous buildup. Oxycodone is also risky in advanced disease. Guidelines recommend cutting the starting dose to 30%-50% in severe hepatic impairment.

Methadone is tricky. It’s broken down by multiple enzymes, so it doesn’t depend on just one pathway. That sounds good-but it also means there’s no clear rule for how to adjust the dose in liver disease. No studies have given doctors a reliable formula. That’s why many avoid it unless they have expert help.

Buprenorphine and fentanyl are better options, but not because they’re safer for the liver. They’re safer because they’re absorbed differently. Buprenorphine can be given as a patch or under-the-tongue tablet, which skips the liver’s first pass. Fentanyl patches work the same way. This means less drug hits the liver upfront. For someone with cirrhosis, this can mean the difference between safe pain control and overdose.

Dosing Adjustments That Actually Work

If you must use opioids in liver disease, start low and go slow. For morphine in early liver disease, reduce the dose by 25%-50% and keep the same dosing schedule. In advanced disease, cut the dose even more-and space doses further apart. Instead of every 4 hours, go every 6 to 8 hours. For oxycodone, start at 30%-50% of the normal dose and wait at least 12 hours before giving another dose. Monitor closely for drowsiness, slow breathing, or confusion.

Never assume a patient’s weight or age tells you the right dose. Liver function matters more. A thin 70-year-old with mild fatty liver might need the same dose as a heavier 45-year-old with no liver issues. The only way to know is to test liver function with blood tests like albumin, bilirubin, and INR-and use scoring systems like Child-Pugh to grade severity.

What Doctors Still Don’t Know

There are big gaps in the science. We don’t have clear dosing rules for hydromorphone, codeine, or tramadol in liver disease. We don’t know how much opioid use contributes to liver cancer risk. We don’t know if stopping opioids helps reverse liver damage caused by gut inflammation. Most studies are small, done in hospital settings, and don’t reflect real-world use over months or years.

Transdermal patches (like fentanyl or buprenorphine) seem promising, but long-term data is lacking. We also don’t know how well naloxone works to reverse overdoses in people with severe liver failure. Their bodies may process the reversal drug slower too.

What Patients Should Watch For

If you have liver disease and are on opioids, watch for these signs: feeling unusually sleepy, difficulty waking up, slow or shallow breathing, confusion, or new muscle twitching. These aren’t normal side effects-they’re red flags. Tell your doctor immediately. Don’t wait until you feel worse. Don’t increase your dose on your own. Don’t take extra pills for breakthrough pain without checking in first.

Ask your doctor: "Is this opioid safe for my liver?" and "What’s my Child-Pugh score?" If they don’t know, ask for a referral to a pain specialist or hepatologist. Many primary care doctors aren’t trained in this. You need someone who understands both liver function and opioid pharmacology.

There’s no perfect opioid for liver disease. But there are safer choices-and there’s a way to use them without putting your life at risk. The key is knowing your liver’s limits and working with a team that respects them.

Can opioids cause more liver damage?

Yes. While opioids aren’t directly toxic to liver cells like acetaminophen, they can make liver disease worse by disrupting the gut microbiome. This leads to increased inflammation and faster scarring, especially in alcohol-related and fatty liver disease. Long-term use may accelerate progression from steatosis to cirrhosis.

Is morphine safe for people with cirrhosis?

Morphine is generally not recommended in moderate to severe cirrhosis. Its metabolites, especially M3G, build up and can cause neurological side effects like seizures. Even with dose reductions, the risk remains high. Safer alternatives like buprenorphine patches are preferred.

Why is oxycodone risky in liver disease?

Oxycodone is broken down by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, both of which become less active in liver disease. This causes the drug to stay in the body much longer-up to 24 hours instead of 3.5. Peak blood levels can rise by 40%, increasing overdose risk. Starting doses must be cut by half or more.

Can I use fentanyl patches if I have liver disease?

Yes, fentanyl patches are often a better choice. Because they deliver the drug through the skin, they avoid the liver’s first-pass metabolism. This reduces the risk of buildup. But you still need careful monitoring-dose adjustments are still needed in severe liver failure.

How do I know if my liver is too damaged for opioids?

Your doctor should check your Child-Pugh score, which uses blood tests (bilirubin, albumin, INR) and signs like ascites or encephalopathy to grade liver function. If you’re Class B or C, opioid use requires major caution. Many experts avoid opioids entirely in Class C unless no other option exists.

Are there non-opioid options for pain in liver disease?

Yes. Acetaminophen is safe up to 2,000 mg per day in most liver disease patients. NSAIDs should be avoided due to kidney and bleeding risks. Non-drug options like physical therapy, nerve blocks, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acupuncture can help manage chronic pain without risking liver damage.