Every year, hundreds of thousands of people in the U.S. end up in the hospital because of something that was supposed to help them: their medication. These aren’t accidents caused by falling down stairs or misdiagnoses. They’re adverse drug events - harm caused directly by drugs, whether from a mistake, a bad reaction, or a dangerous interaction. And the scary part? Most of them are preventable.

What Exactly Is an Adverse Drug Event?

An adverse drug event (ADE) is any injury that happens because of a medication. It doesn’t matter if the drug was taken correctly or not. If a patient gets hurt, and the medicine played a role, it’s an ADE. This includes everything from mild rashes to life-threatening bleeding or overdoses.

The key difference between an ADE and a general adverse event is that ADEs are tied specifically to drugs. A broken hip after a fall isn’t an ADE. But if that fall happened because the patient got dizzy from a new blood pressure pill, then it is. The Institute of Medicine first brought this into the spotlight in 2000, revealing that medication errors alone caused at least 7,000 deaths in U.S. hospitals each year. That number hasn’t gone down - it’s just gotten more complex.

Today, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reports that ADEs lead to 3.5 million doctor visits, 1 million emergency room trips, and 125,000 hospital admissions annually in the U.S. That’s more than the total number of car accident hospitalizations each year. And it’s not just hospitals - ADEs happen in homes, clinics, and nursing homes too.

The Five Main Types of Adverse Drug Events

Not all ADEs are the same. They fall into five clear categories, each with its own cause and risk pattern.

- Adverse drug reactions - These happen when your body responds badly to a drug at a normal dose. Think of it like an unexpected side effect. For example, a statin might cause muscle pain even when taken exactly as prescribed.

- Medication errors - These are preventable mistakes. A doctor prescribes the wrong dose. A pharmacist gives the wrong pill. A nurse administers the drug at the wrong time. These aren’t side effects - they’re human or system failures.

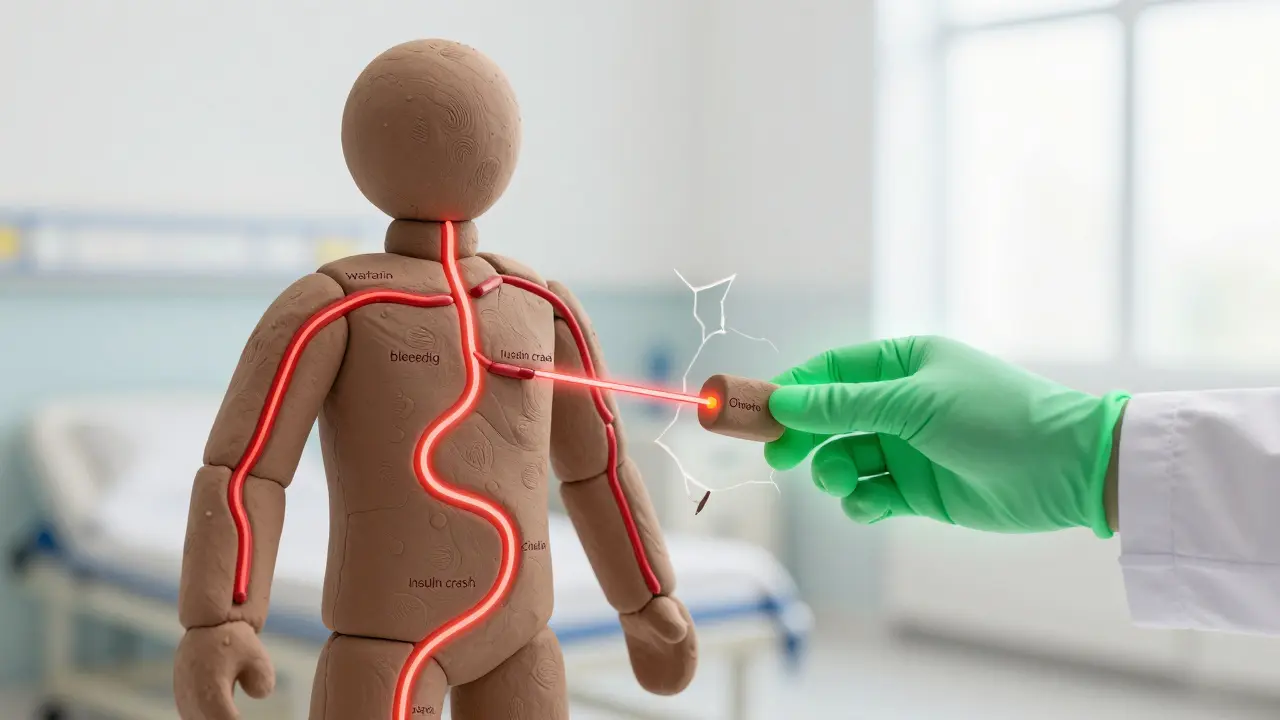

- Drug-drug interactions - When two or more medications mix in a harmful way. For instance, taking warfarin with certain antibiotics can turn a blood thinner into a bleeding risk.

- Drug-food interactions - Certain foods change how your body handles drugs. Grapefruit juice, for example, can make cholesterol meds like simvastatin dangerously potent.

- Overdoses - Either accidental (like taking two pills by mistake) or intentional. Opioids are the biggest concern here, responsible for 40% of medication-related deaths in the U.S.

Doctors and pharmacists often classify drug reactions even further. Type A reactions are predictable and dose-related - they make up 80% of all ADEs. Type B reactions are rare, unpredictable, and often allergic. Type C builds up over time, like kidney damage from long-term NSAID use. Type D shows up months or years later, like cancer from certain chemotherapy drugs. Type E happens when you stop taking a drug - think rebound high blood pressure after suddenly quitting beta-blockers.

The Big Three: Most Dangerous ADEs in the U.S.

Not all ADEs are created equal. Three types cause the most harm, and they’re all tied to common medications:

- Anticoagulants (like warfarin) - These thin the blood to prevent strokes, but they’re also the #1 cause of ADE-related hospitalizations. Warfarin alone leads to 33,000 emergency visits each year. Why? It has a narrow window between working and causing bleeding. If your INR (a blood test that measures clotting time) is off by just a little, you’re at risk. Studies show that 35% of outpatient INR tests are outside the safe range.

- Diabetes medications (especially insulin) - Hypoglycemia - dangerously low blood sugar - is the biggest problem. Around 100,000 emergency visits each year are from insulin-related low blood sugar. More than half of those patients are over 65. Older adults are more sensitive to insulin, and many don’t recognize the early signs of low sugar until it’s too late.

- Opioids - Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are behind 70,601 of the 107,622 drug overdose deaths in 2021. Many of these aren’t recreational - they’re from prescriptions that were too strong, too long, or not monitored properly. The CDC calls this a public health crisis, and for good reason.

These three categories alone account for more than half of all serious ADEs in hospitals. That’s why the Department of Health and Human Services made them the top targets in its 2014 National Action Plan for ADE Prevention.

How to Prevent Adverse Drug Events - Proven Strategies

Preventing ADEs isn’t about hoping for the best. It’s about using systems that have been tested and proven to work. Here’s what actually reduces harm:

- Medication reconciliation - This means comparing your current meds with what you were taking before you entered the hospital or changed providers. A 2020 study showed this cuts post-discharge ADEs by 47%. It sounds simple, but it’s often skipped. One patient might be on five drugs at home, but only three get listed on admission. The other two? Forgotten. That’s how dangerous interactions slip through.

- Electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) - Paper prescriptions lead to misreads and wrong doses. E-prescribing cuts errors by 48%, according to AHRQ. Systems now flag potential interactions, duplicate therapies, and incorrect doses before the prescription even leaves the doctor’s computer.

- Pharmacist-led medication reviews - Pharmacists don’t just fill prescriptions. They’re trained to spot problems. Medication Therapy Management (MTM) services, where pharmacists sit down with patients to review all their meds, identify an average of 4.2 medication problems per person. That translates to a 32% drop in ADE risk.

- Deprescribing - Sometimes, the best treatment is stopping a drug. Especially in older adults, long-term use of anticholinergics (used for allergies, overactive bladder, or depression) can cause confusion, falls, and dementia-like symptoms. The VA’s structured deprescribing protocols reduced these ADEs by 40% in elderly patients.

- Patient education - If you don’t understand why you’re taking a drug, how to take it, or what side effects to watch for, you’re at risk. A 2021 Cochrane review found that clear, simple education improves adherence by 22%. That means fewer missed doses, fewer extra pills, and fewer mistakes.

Technology is helping too. The Veterans Affairs system uses real-time dashboards that alert doctors if a patient’s warfarin dose puts them at risk for bleeding. They’ve cut those events by 28%. They also use pharmacogenomic testing - checking a patient’s DNA to see how they’ll process certain drugs. For clopidogrel (a blood thinner), this testing reduced ADEs by 35% because it identified patients who couldn’t activate the drug properly.

What’s Changing Now - And What’s Next

The fight against ADEs is evolving. In 2023, the National Action Plan was updated to include new high-risk drugs like monoclonal antibodies and antipsychotics, which caused 12,000 serious events in 2022. The WHO’s global campaign, Medication Without Harm, reduced harm by 18% between 2017 and 2022 - a good start, but still short of the 50% goal.

One of the biggest advances is artificial intelligence. At Johns Hopkins, AI algorithms analyze 50+ patient factors - age, lab results, other meds, genetics - to predict who’s most likely to have an ADE. In pilot programs, this cut ADEs by 17%. That’s not magic - it’s data-driven prevention.

But progress isn’t uniform. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals have fully integrated clinical decision support in their electronic records. And only 15% of primary care doctors routinely screen elderly patients for inappropriate medications, even though guidelines like the Beers Criteria have been around for years.

The future? Personalized medicine. Right now, less than 5% of patients get pharmacogenomic testing. But by 2027, that number could jump to 30%. Imagine knowing before you even take a drug whether your body will handle it safely. That’s not science fiction - it’s the next step in making medications truly safer.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a hospital or a pharmacist to start preventing ADEs. Here’s what you can do right now:

- Keep a current list of every medication you take - including vitamins, supplements, and over-the-counter drugs.

- Ask your doctor: “Why am I taking this? What happens if I stop?”

- Ask your pharmacist: “Could this interact with anything else I’m taking?”

- Know the signs of a bad reaction - unusual bleeding, extreme fatigue, confusion, swelling, or sudden dizziness.

- Don’t skip follow-up blood tests. If you’re on warfarin, insulin, or lithium, those tests aren’t optional.

Medications save lives. But they can also hurt - sometimes badly. The difference between safety and harm isn’t luck. It’s awareness, communication, and systems that don’t allow mistakes to slip through.

What’s the difference between an adverse drug reaction and an adverse drug event?

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a specific type of ADE - it’s a harmful response to a drug taken correctly at normal doses. An adverse drug event (ADE) is broader - it includes ADRs, but also medication errors, overdoses, and interactions. All ADRs are ADEs, but not all ADEs are ADRs.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause adverse drug events?

Yes. Common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and even antacids can cause ADEs. Long-term use of NSAIDs can lead to stomach bleeding or kidney damage. Taking too much acetaminophen can cause liver failure. Many people don’t realize OTC meds carry risks, especially when mixed with prescription drugs or alcohol.

Are older adults more at risk for adverse drug events?

Absolutely. Older adults are more sensitive to drugs because their bodies process them slower. They often take multiple medications, increasing interaction risks. About 60% of insulin-related hypoglycemia ER visits involve people over 65. Drugs like anticholinergics and benzodiazepines can cause confusion, falls, and memory loss in seniors - yet they’re still prescribed too often.

How do drug interactions happen?

Drugs can interfere with each other in three ways: by changing how fast your body breaks them down, by competing for the same receptors, or by affecting the same organ system. For example, grapefruit juice slows the breakdown of some statins, causing toxic levels. Antibiotics can make warfarin stronger, increasing bleeding risk. Even common supplements like St. John’s wort can reduce the effectiveness of birth control pills and antidepressants.

What role do pharmacists play in preventing ADEs?

Pharmacists are frontline defenders. They review prescriptions for errors, check for interactions, educate patients, and manage complex regimens. In VA hospitals, pharmacist-led anticoagulation clinics reduced major bleeding by 60% compared to standard care. In community pharmacies, Medication Therapy Management services resolve an average of 4.2 medication problems per patient - directly preventing harm.

Is there a way to predict if I’m at risk for an ADE?

Yes, but it’s not yet standard everywhere. AI tools are being used in hospitals to predict ADE risk by analyzing your age, lab results, current meds, and medical history. Some clinics now offer pharmacogenomic testing - a simple cheek swab that shows how your body metabolizes certain drugs. This can prevent problems before they start, especially with blood thinners, antidepressants, and pain meds.

Final Thoughts

Adverse drug events aren’t inevitable. They’re symptoms of systems that are too fragmented, too slow, or too reliant on memory. The tools to prevent them exist - e-prescribing, pharmacist reviews, patient education, AI alerts, and genetic testing. The challenge isn’t finding solutions. It’s using them consistently, everywhere.

Every time a patient is discharged without a full med list, every time a doctor skips checking for interactions, every time a senior is given a drug that causes dizziness - that’s a preventable event. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s progress. And progress starts with awareness, questions, and the courage to speak up.