Acute interstitial nephritis isn’t something most people hear about until it happens to them-or someone they know. It’s not a common diagnosis, but when it hits, it can turn a routine medication into a silent threat to kidney function. This isn’t about rare side effects. It’s about real, documented risks tied to drugs you might be taking right now: heartburn pills, antibiotics, pain relievers. And the damage doesn’t always go away.

What Exactly Is Acute Interstitial Nephritis?

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is an inflammation of the tissue between the kidney’s filtering units-the tubules and interstitium. Think of it like swelling in the spaces around the kidney’s workhorses. When this happens, the kidneys can’t filter waste properly, leading to a sudden drop in function. It’s not glomerulonephritis. It’s not a urinary tract infection. It’s a reaction deep inside the kidney structure, often triggered by drugs.

It shows up as acute kidney injury: rising creatinine, lower urine output, fatigue, nausea. Sometimes it’s silent until a routine blood test flags it. About 5 to 15% of all cases of sudden kidney failure in hospitals turn out to be AIN. And in most of those cases-60 to 70%-it’s caused by a medication.

The Top Culprits: Which Drugs Are Really to Blame?

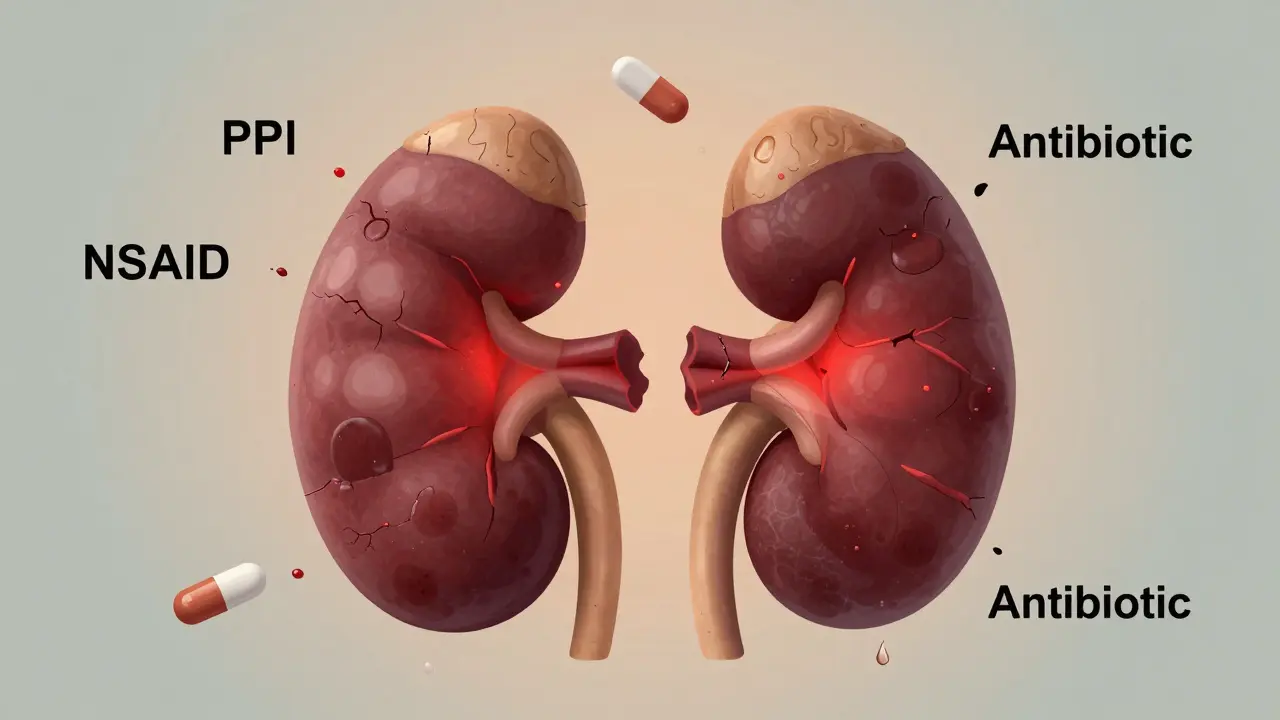

Over 250 medications have been linked to AIN. But three classes stand out in today’s clinical landscape.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole: Once considered safe for long-term use, these heartburn drugs are now the second most common cause of AIN. Studies show 12 cases per 100,000 people annually from PPIs alone. The risk rises after 6 months of use and peaks around 12 to 18 months. Surprisingly, even though the inflammation may be milder than with antibiotics, recovery is less complete-only 50 to 60% of patients regain full kidney function.

- Antibiotics: Penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, and even ciprofloxacin still make up about a third of cases. These tend to hit fast-symptoms often appear within 10 days. Classic signs like fever, rash, and eosinophilia show up more often here, but not always. Even without those classic signs, the damage can still be serious.

- NSAIDs: Ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac. These account for nearly half of all drug-induced AIN cases. What’s tricky is that they don’t usually cause the typical allergic reactions. No rash. No fever. Just slow, steady kidney decline. Patients are often older, on multiple meds, and already have some kidney stress. Proteinuria can be severe-sometimes reaching nephrotic levels. Recovery is slower, and the chance of permanent damage is higher than with any other trigger.

There’s also a growing group: immune checkpoint inhibitors used in cancer treatment. These are newer, less common, but their mechanism is different-more autoimmune than allergic. They’re on the rise, and so are their kidney side effects.

Why Diagnosis Is So Often Delayed

Most patients don’t realize their kidney trouble is drug-related. Symptoms look like the flu: tired, nauseous, achy, maybe a low fever. Doctors often mistake it for a urinary infection, especially if there’s mild blood in the urine or a slight rise in creatinine. The American Kidney Fund reports patients wait 2 to 4 weeks on average before getting the right diagnosis.

The problem? There’s no simple blood test or scan that confirms AIN. Urine tests might show eosinophils, but that’s only 50% reliable. A gallium scan? Rarely used. The only way to know for sure is a kidney biopsy. That’s invasive. That’s scary. So many doctors wait, hoping it’ll resolve on its own.

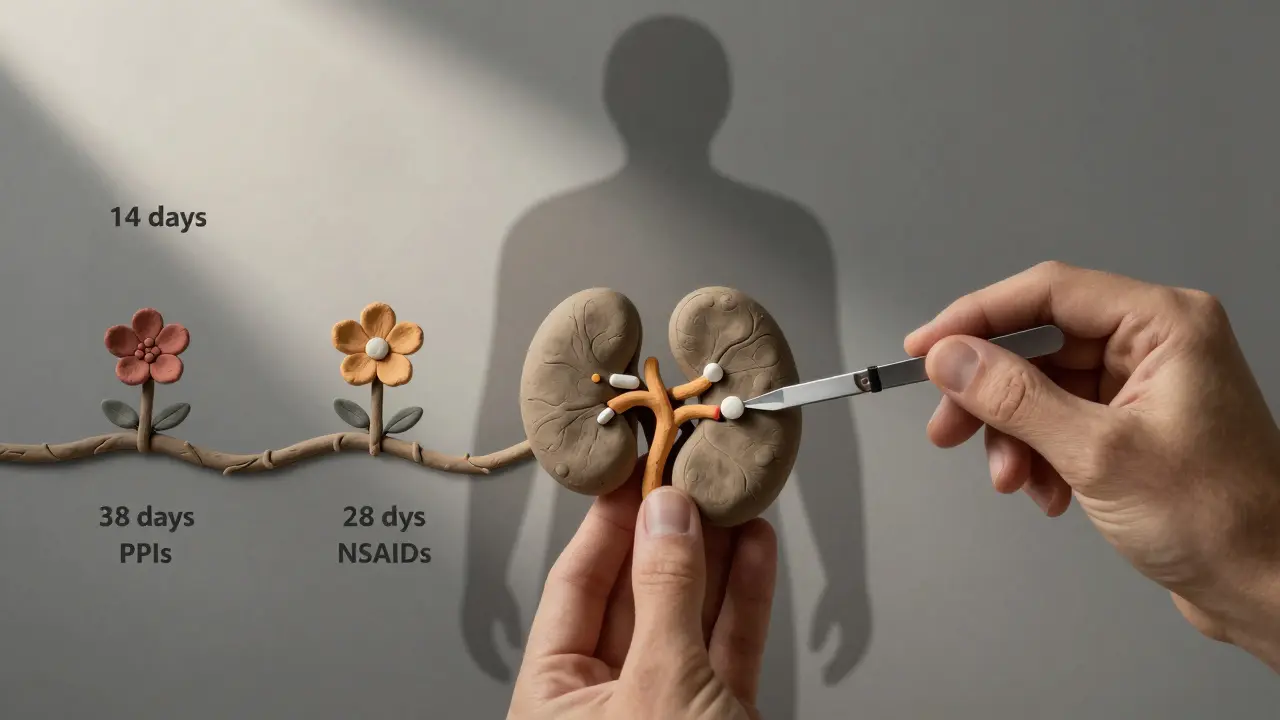

But waiting is dangerous. Research shows if you get the biopsy within 7 days of symptoms starting, your chance of full recovery jumps by 35%. After 14 days? The odds drop. Permanent scarring begins to set in.

Recovery: What Actually Happens After Stopping the Drug?

Stopping the drug is the single most important step. In fact, most guidelines say it must happen within 24 to 48 hours of suspicion. And it works-fast.

A Medscape survey of 120 patients found 65% felt better within 72 hours of stopping the offending medication. That’s rapid. But feeling better doesn’t mean the kidneys are healed.

Recovery timelines vary wildly by drug:

- Antibiotics: Median recovery in 14 days

- NSAIDs: Median recovery in 28 days

- PPIs: Median recovery in 35 days

And here’s the hard truth: even if kidney function improves, it doesn’t always return to normal. In one study, 42% of patients still had reduced kidney function (eGFR below 60) six months later. That’s stage 2 or 3 chronic kidney disease. For NSAID-induced cases, the risk of progressing to chronic disease hits 42%. For PPIs, it’s around 30%. Antibiotics? Closer to 20%.

One patient case from the American Kidney Fund tells the story: a 63-year-old woman on omeprazole for 18 months developed AIN. She needed dialysis for three weeks. Her eGFR recovered to 45 after a year. She’s stable-but not back to baseline. That’s not rare.

Do Steroids Help? The Controversy

This is where things get messy. Should you take steroids?

There are no large randomized trials proving they work. But in practice, nephrologists use them-especially when kidney function is severely low (eGFR under 30) or if it keeps dropping after stopping the drug.

The typical protocol? Methylprednisolone at 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight for 2 to 4 weeks, then slowly tapering to prednisone over 6 to 8 weeks. The European Renal Association says this is common practice, even without perfect evidence.

Why? Because early intervention seems to help. Dr. Ronald J. Falk, a leading kidney expert, says steroids improve outcomes in severe cases. The risk of side effects from short-term steroids is low compared to the risk of permanent kidney damage.

But steroids aren’t for everyone. If you stop the drug and your creatinine drops steadily over a week? You probably don’t need them. If you’re still declining after 72 hours? That’s the signal.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not random. Certain patterns show up again and again:

- Age 65+: Risk jumps from 5 cases per 100,000 in young adults to 22 cases per 100,000 in seniors.

- Multiple medications: Taking five or more drugs makes you 3.2 times more likely to develop AIN.

- Preexisting kidney issues: Even mild CKD increases vulnerability.

- Long-term PPI use: More than 6 months? You’re in the danger zone.

And it’s not just about quantity-it’s about combinations. A senior on omeprazole, lisinopril, and ibuprofen? That’s a perfect storm.

What’s Changing Now-and What to Watch For

The FDA issued a safety alert in 2021 after reviewing over 1,200 AIN cases linked to PPIs between 2011 and 2020. That’s not a small number. And the trend is still rising. Between 2010 and 2020, drug-induced AIN cases increased by 27%, mostly because of PPI overuse.

Researchers are working on alternatives to biopsy. A promising biomarker-urinary CD163-showed 89% sensitivity in a 2022 study. If validated, it could mean a simple urine test replaces the needle in the future.

But for now, the best defense is awareness. If you’re on a PPI for heartburn and you’re over 60, ask: Do I still need it? If you’re on NSAIDs daily for arthritis, could you cut back? If you’ve been on antibiotics recently and now feel off, get your creatinine checked.

What You Can Do

Don’t panic. But do pay attention.

- If you’re on long-term PPIs, talk to your doctor about whether you still need them. Many people take them years longer than necessary.

- If you’re on NSAIDs daily, consider alternatives like acetaminophen or physical therapy for pain.

- If you feel unusually tired, nauseous, or notice less urine output after starting a new drug, get bloodwork done. Don’t wait.

- If your doctor suspects AIN, push for a kidney biopsy if kidney function isn’t improving after stopping the drug.

AIN isn’t inevitable. But it’s not rare either. And the longer we ignore the link between common medications and kidney damage, the more people will end up with permanent kidney problems.