Polyposis Bleeding Risk Estimator

Polyposis is a group of hereditary conditions that cause numerous polyps to form throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These polyps vary in size, histology, and malignant potential, and they often set the stage for gastrointestinal bleeding. Understanding the link between polyposis and bleeding helps clinicians intervene before severe anemia or cancer develops.

Why Polyps Bleed: The Pathophysiology

Polyps erode the mucosal surface, disrupt normal blood vessels, and can ulcerate. When a polyp outgrows its blood supply, necrosis occurs, exposing submucosal vessels. This process is amplified in certain polyp types:

- Adenomatous polyps are dysplastic growths that tend to have a thick stalk and a rich capillary network, making them prone to oozing during friction.

- Hamartomatous polyps (e.g., Peutz‑Jeghers) contain ectopic tissue that can cause focal ulceration and intermittent bleeding.

The recurrent micro‑bleeds often go unnoticed until they accumulate enough blood loss to lower hemoglobin, manifesting as iron‑deficiency anemia.

Key Genetic Drivers

Most polyposis syndromes are tied to single‑gene mutations. The APC gene mutation underlies Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), leading to hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps. In Peutz‑Jeghers syndrome, STK11 loss drives hamartomatous formations. These genetic clues not only predict polyp burden but also help estimate bleeding risk: larger polyp loads generally increase the odds of mucosal injury.

Clinical Presentation: From Occult Blood to Overt Bleeds

Patients with polyposis may present in three common ways:

- Occult blood detected on stool guaiac tests during routine surveillance.

- Chronic fatigue and pallor driven by Iron deficiency anemia, often confirmed by low ferritin and microcytic red cells.

- Acute melena or hematochezia when a large polyp tears.

Because bleeding can be intermittent, clinicians rely on serial fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) and iron studies to flag hidden loss.

Diagnostic Pathway

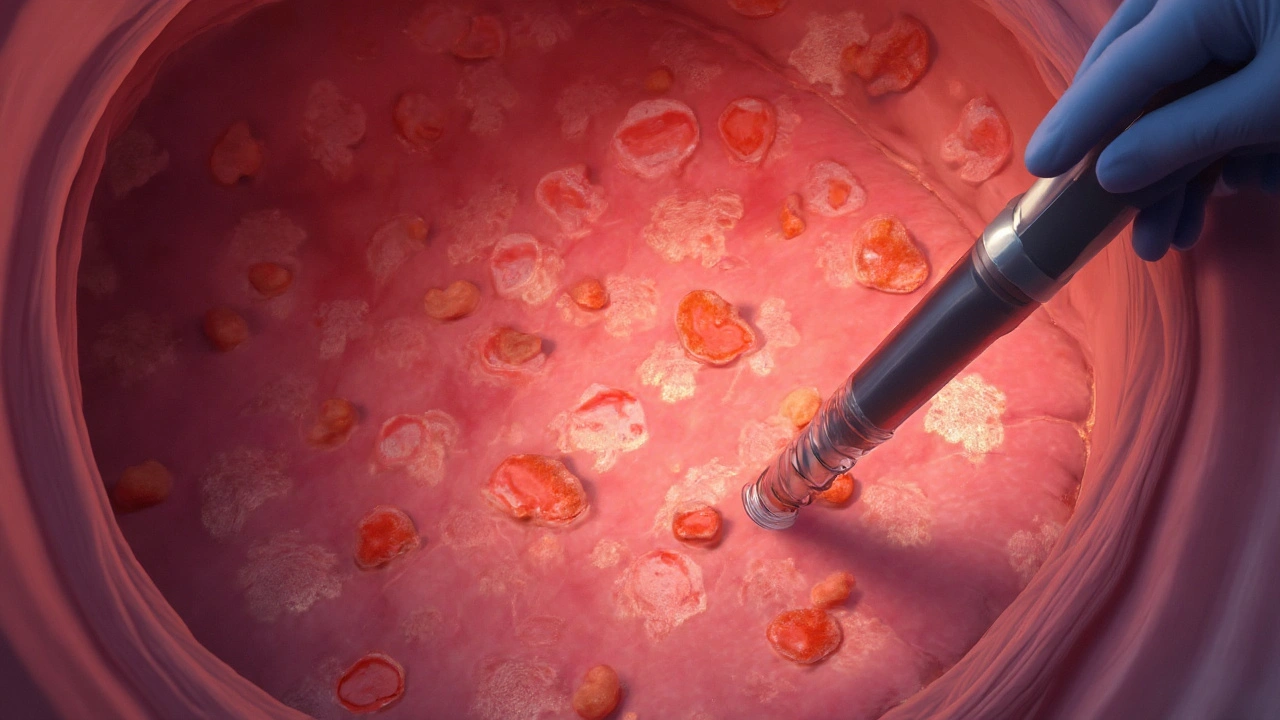

The cornerstone of diagnosis is Colonoscopy, which allows direct visualization, biopsy, and immediate polypectomy. In patients with extensive small‑bowel polyps, capsule endoscopy or double‑balloon enteroscopy may be required.

Key steps:

- Baseline complete blood count (CBC) and iron panel.

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) to detect occult blood.

- High‑resolution colonoscopy with dye spray (chromoendoscopy) for flat lesions.

- Genetic testing for APC, STK11, and other relevant mutations when family history suggests hereditary syndrome.

When bleeding persists despite endoscopic therapy, imaging such as CT angiography can localize active hemorrhage.

Management Strategies

Therapeutic goals focus on stopping bleeding, preventing recurrence, and reducing cancer risk.

- Endoscopic polypectomy: Snare or EMR (endoscopic mucosal resection) removes bleeding polyps and reduces future bleed sources.

- Pharmacologic control: Proton‑pump inhibitors lower gastric acidity, minimizing ulceration on upper GI polyps. In select cases, non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) avoidance helps.

- Iron replacement: Oral ferrous sulfate or IV iron (for severe anemia) restores hemoglobin levels.

- Surgical options: Colectomy is recommended for FAP patients with >100 polyps or refractory bleeding.

Regular surveillance guidelines-typically colonoscopy every 1‑2 years-are vital to catch new bleeding polyps early.

Comparison of Major Polyposis Syndromes

| Condition | Typical Polyp Type | Average Polyp Count | Bleeding Frequency | Management Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) | Adenomatous | >1,000 | High (30‑45% develop anemia) | Colectomy + endoscopic surveillance |

| Peutz‑Jeghers Syndrome | Hamartomatous | 20‑100 | Moderate (10‑20% occasional melena) | Polypectomy + mucosal protection |

| Juvenile Polyposis | Juvenile (hyperplastic) | 5‑50 | Low‑moderate (5‑15%) | Endoscopic removal, genetic counseling |

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Understanding polyposis opens doors to broader topics such as colorectal cancer prevention, hereditary cancer genetics, and minimally invasive endoscopic techniques. Readers interested in deeper dives might explore:

- How APC mutation dosage influences cancer onset.

- Advanced endoscopic tools like cold snare polypectomy.

- Psychosocial support for families coping with hereditary syndromes.

Each of these areas builds on the core link between polyps and bleeding, allowing a more comprehensive care plan.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes polyps to bleed?

Polyps can ulcerate, erode superficial blood vessels, or undergo necrosis when they outgrow their blood supply. The resulting exposure of submucosal vessels leads to slow ooze or, in larger lesions, brisk bleeding.

How often should someone with FAP undergo colonoscopy?

Guidelines recommend colonoscopy every 1‑2 years starting in early adolescence (age 10‑12) for FAP carriers. The frequency may increase if new polyps appear or if bleeding episodes occur.

Can dietary changes reduce bleeding risk?

While diet cannot eliminate polyps, a high‑fiber, low‑red‑meat diet may lessen mucosal irritation and help maintain regular bowel movements, which can lower mechanical stress on polyps and reduce bleed episodes.

When is surgery needed for polyposis‑related bleeding?

Surgery is considered when polyp burden exceeds what endoscopy can safely manage, when bleeding is refractory to repeat polypectomy, or when there is a high colorectal cancer risk (e.g., >100 adenomatous polyps in FAP).

What are the red‑flag signs of severe GI bleeding?

Sudden onset of black tarry stools (melena), bright red blood per rectum (hematochezia), rapid drop in hemoglobin, dizziness, or fainting are emergency signals that require urgent evaluation.

How reliable is FIT for detecting bleeding in polyposis patients?

FIT is highly sensitive for occult blood, but false negatives can occur if bleeding is intermittent. It works best as part of a surveillance protocol combined with periodic colonoscopy.

Are there preventive medications for polyposis?

Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) celecoxib has shown modest polyp‑size reduction in FAP, but benefits must be weighed against cardiovascular risks. Calcium carbonate and aspirin are being studied but are not yet standard.